The region between Nice and Cannes is located along the French Mediterranean coast (French Riviera). A quite dense urban belt is located aside the shore, where all hilly catchments finish their way to the sea.

On 3rd October 2015, severe rainfalls triggered dramatic flash floods. Twenty people died, about 550-650 million € of losses were observed, as well as cascading complications on transportation, communication and energy networks. Within the project NAIAD, this event will be used as a calibration case to study torrential flood hazards and risks and the effects on ecosystems.

Brague basin:

• 61 km²,

• rural headwaters,

• forested central part and urban lowlands

Nature Based Solutions management is more than a technical problem: specific design and integrated decision-making frameworks are needed. From a more global point of view, choice of Nature Based Solutions and effectiveness assessment require specific principles mixing pluridisciplinary quantitative and qualitative criteria and indicators. It is important to note that the choice and definition of NbS’ effectiveness indicators highly depend on time, spatial scales and decision-making contexts. La Brague DEMO proposes some pathways to contribute to this objective. It is indeed essential to build and choose solutions on strong physical evidences, accepted and understood by traditional (technical) flood risk managers, but also to consider other environmental, social features and to make them accepted and implemented by stakeholders.

Three NAIAD project partners are involved in the Brague Demonstration Site:

1. IRSTEA performed analysis regarding biophysical hazards and risks:

• The forest vulnerability to wildfire is studied as well as the cascading process of flood aggravated by wildfire. We demonstrate that although wildfire hazards were high to very high, burnt areas were limited by existing very efficient firefighter organization. Only during extremely dry and hot summer, they may be overwhelmed and large scale fires may occur aggravating during a few years’ run-off and erosion generation.

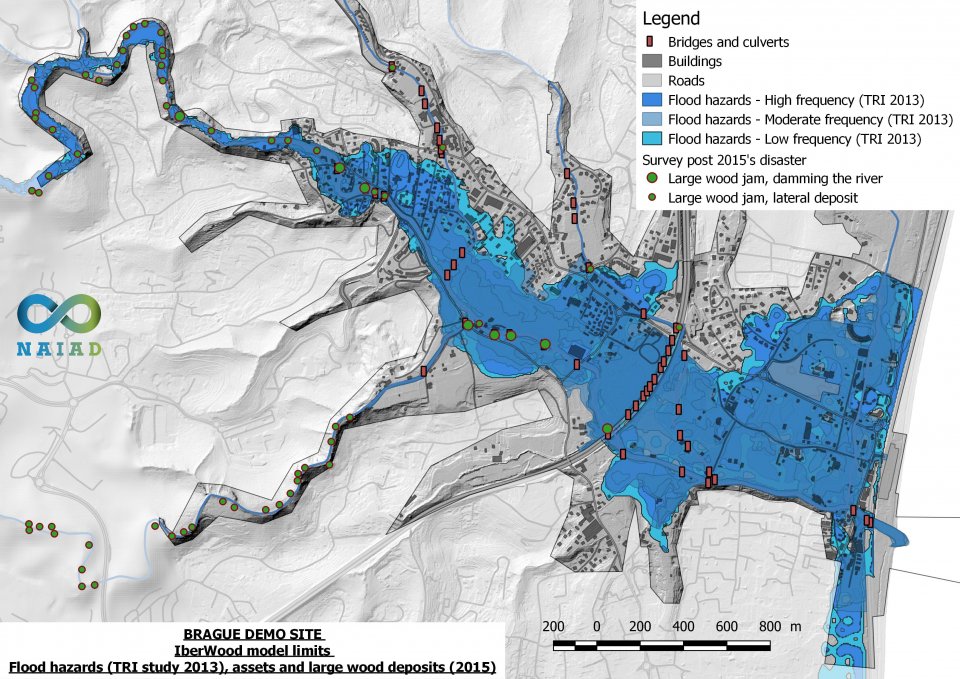

• Simple and advanced flood modelling are performed and demonstrate that the traditional use of retention basins and channelization of water courses fall in defect facing such extreme events as October 2015 flood. A new framework of cost-effectiveness analysis is developed to appraise different civil engineering, NbS and hybrid protection strategies and published in the journal River Research and Application (draft: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/147624/1/mainrevRRA.pdf). Advanced numerical modelling simulations using the software IberWood are still going on;

• To better understand hazard and risk components, specific developments about physical vulnerability in the context of torrential floods have been done;

• A global framework for NbS effectiveness assessment based on a multicriteria decision-aiding and global integrated approaches have been proposed.

2. CCR is using and improving its runoff-damage model to compute the efficacy of small retention areas in protecting the assets located in the basin.

3. UNS-IMREDD is performing an economic valuation of NbS efficiency and a survey on public perception of flood risks and NbS for flood mitigation.

The whole consortium has organized regular public workshops to gather local information, to analyse decision-making contexts, to inform about NAIAD’s approach and results and to raise stakeholders’ participation in flood mitigation and management process.

- Developing climate change adaptation; improving risk management and resilience

- Better protection and restoration of coastal ecosystems

- Flood peak reduction

- Reduce drought risk

- Reduce flood risk

- Increase awareness of NBS solution & their effectiveness and co benefits

- Increase population & infrastructures protected by NBS

- Increase stakeholder awareness & knowledge about NBS

- Increase willingness to invest in NBS

Nature Based Solutions can protect but their implementation requires specific management rules. For instance, forests (including riparian forests) have recognized positive effects on hydraulics, ecological habitats preservation, etc. However, they remain vulnerable (to wildfires for instance) and may induce drawbacks. A realistic and objective assessment is proposed in NAIAD.

From a technical point of view, a strong and quite precise take-home-message of our demo site is that large wood recruitment and clogging of bridges cannot be dealt with by annual management of dead and titling trees: The Brague management agency has been performing such a management for 20 years and nonetheless more than 3000 trees were recruited and transported downstream during 2015 flood. They were mostly living, healthy trees but the flood event was just too extreme. The relevant solution, which is also cheaper on the long term, is to implement large-woodtrapping facilities upstream of bottleneck sections (bridges, dams) and to let natural, un-managed upstream forest area. This has the additional advantage of improving environmental status of the rivers. In essence and at the end, it is therefore cheaper, more sustainable, efficient and better for nature.

A broader message is that in rivers hit by Mediterranean thunderstorms of high magnitude, even high ambition on retention measures in the upper and mid-catchment is insufficient to prevent flooding of downstream floodplain: a sufficiently large corridor must be maintained for such rivers to convey flows down to the sea or to the downstream bigger river. Such corridor can be natural and/or comprise several flood resilient activities, however, building assets in those corridors is a long lasting constraint and people working and living there will always expect higher information level and complain to local authorities if damage occurs. Then, land-use, land cover control and protecting such areas may become extremely expensive and even sometimes not feasible regarding high magnitude events. Buying such vulnerable assets to then remove (destroy) them to reduce exposure is another very expensive but existing solution. On the contrary, large corridors are resilient, sustainable, provide numerous co-benefits, but require to somehow change long-term land-use strategies and to make them accepted by local stakeholders.

Nature Based Solutions management is more than a technical problem: specific design and integrated decision-making frameworks are needed. From a more global point of view, choice of Nature Based Solutions and effectiveness assessment require specific principles mixing pluridisciplinary quantitative and qualitative criteria and indicators. It is important to note that the choice and definition of NbS’ effectiveness indicators highly depend on time, spatial scales and decision-making contexts. La Brague DEMO proposes some pathways to contribute to this objective. It is indeed essential to build and choose solutions on strong physical evidences, accepted and understood by traditional (technical) flood risk managers, but also to consider other environmental, social features and to make them accepted and implemented by stakeholders.

Thanks to NAIAD, local authorities have the opportunity to take benefit from more accurate and integrated hazard studies. The role of large wood in flood hazard is a particular source of concern and has been thoroughly studied by IRSTEA with proposition of solutions. Decision-making regarding the priority in implementing measures in the upper and lower parts of the catchment are clarified by the NAIAD’s analysis as well as perceptions and visions of citizens and stakeholders on flood risks and mitigation. Assessing the efficacy of Nature Based Solutions is a core objective and contribution in NAIAD. The goal is to analyse both technical, physical, economic and environmental issues: this effectiveness is analysed on la Brague Demonstration site thanks to an original framework and methodology combining deterministic, quantitative approaches coming from engineering sciences (hydraulics, hydrology, civil engineering, etc.) and also decision sciences to consider sometimes more qualitative NbS’ co-benefits.

No Nature Based Solutions used for flood risk management can be considered as effective if their effect on phenomenon is not demonstrated and quantified. Analyses have been processed in order to quantify, for instance, the effect of protection forest. From a technical point of view, the ambition consists in implementing “giving-room-tothe-river” and upstream retention measures was, so far, smaller and not adjusted with the very high risk threatening the catchment. The habit to rely on retention basins and grey-engineering concrete channel remains deeply established and NAIAD aims to promote and to help change the traditional paradigm. It therefore provides evidences of their irrelevance and the more diverse and relevant benefit and co-benefits of NbS-based strategies.

Nature Based Solutions can protect but their implementation requires specific management rules. For instance, forests (including riparian forests) have recognized positive effects on hydraulics, ecological habitats preservation, etc. However, they remain vulnerable (to wildfires for instance) and may induce drawbacks. A realistic and objective assessment is proposed in NAIAD. From a technical point of view, a strong and quite precise take-home-message of our demo site is that large wood recruitment and clogging of bridges cannot be dealt with by annual management of dead and titling trees: The Brague management agency has been performing such a management for 20 years and nonetheless more than 3000 trees were recruited and transported downstream during 2015 flood. They were mostly living, healthy trees but the flood event was just too extreme. The relevant solution, which is also cheaper on the long term, is to implement large-woodtrapping facilities upstream of bottleneck sections (bridges, dams) and to let natural, un-managed upstream forest area. This has the additional advantage of improving environmental status of the rivers. In essence and at the end, it is therefore cheaper, more sustainable, efficient and better for nature.

A broader message is that in rivers hit by Mediterranean thunderstorms of high magnitude, even high ambition on retention measures in the upper and mid-catchment is insufficient to prevent flooding of downstream floodplain: a sufficiently large corridor must be maintained for such rivers to convey flows down to the sea or to the downstream bigger river. Such corridor can be natural and/or comprise several flood resilient activities, however, building assets in those corridors is a long lasting constraint and people working and living there will always expect higher information level and complain to local authorities if damage occurs. Then, land-use, land cover control and protecting such areas may become extremely expensive and even sometimes not feasible regarding high magnitude events. Buying such vulnerable assets to then remove (destroy) them to reduce exposure is another very expensive but existing solution. On the contrary, large corridors are resilient, sustainable, provide numerous co-benefits, but require to somehow change long-term land-use strategies and to make them accepted by local stakeholders.

Nature Based Solutions management is more than a technical problem: specific design and integrated decision-making frameworks are needed. From a more global point of view, choice of Nature Based Solutions and effectiveness assessment require specific principles mixing pluridisciplinary quantitative and qualitative criteria and indicators. It is important to note that the choice and definition of NbS’ effectiveness indicators highly depend on time, spatial scales and decision-making contexts. La Brague DEMO proposes some pathways to contribute to this objective. It is indeed essential to build and choose

solutions on strong physical evidences, accepted and understood by traditional (technical) flood risk managers, but also to consider other environmental, social features and to make them accepted and implemented by stakeholders.

Guillaume Piton:

|